Books

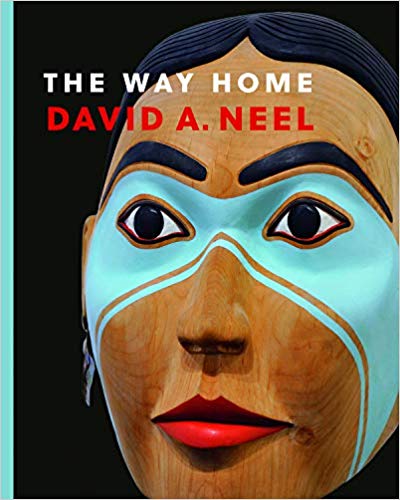

The Way Home

Published: 2019

David Neel was an infant when his father, a traditional Kwakiutl artist, returned to the ancestors, triggering a series of events that would separate David from his homeland and its rich cultural traditions for twenty-five years. When the aspiring photographer saw a mask carved by an ancestor in a Texas museum, the encounter inspired him to return home and follow in his father’s footsteps. Drawing on memory, legend, and his own art, Neel recounts his struggle to reconnect with his culture and become an accomplished Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw artist. His memoir is a testament to the strength of the human spirit to overcome great obstacles and to the power and endurance of Indigenous culture and art.

An excerpt from the book:

In the time of myths there was a Thunderbird who had a young son, and they lived in the land of the Kwakiutl. One day the Thunderbird was called home to the sky-world and he flew away, never to return. The boy, lacking the guidance of his father, wandered far from home until he didn't know from whence he came. After four years his grandfather came to him in a vision, wearing the mask of Tsegame - the Great Magician of the Red Cedar bark. He told him that his people were waiting for him and it was time to go home. The boy began the long journey home, and when he got there he found that he had been away not just a few years but two and half decades. Soon he met other descendants of the Thunderbird and they taught him the ways of their people. The boy stayed in the land of his ancestors, raised a family and eventually he transformed into a Thunderbird like his father.

Summary

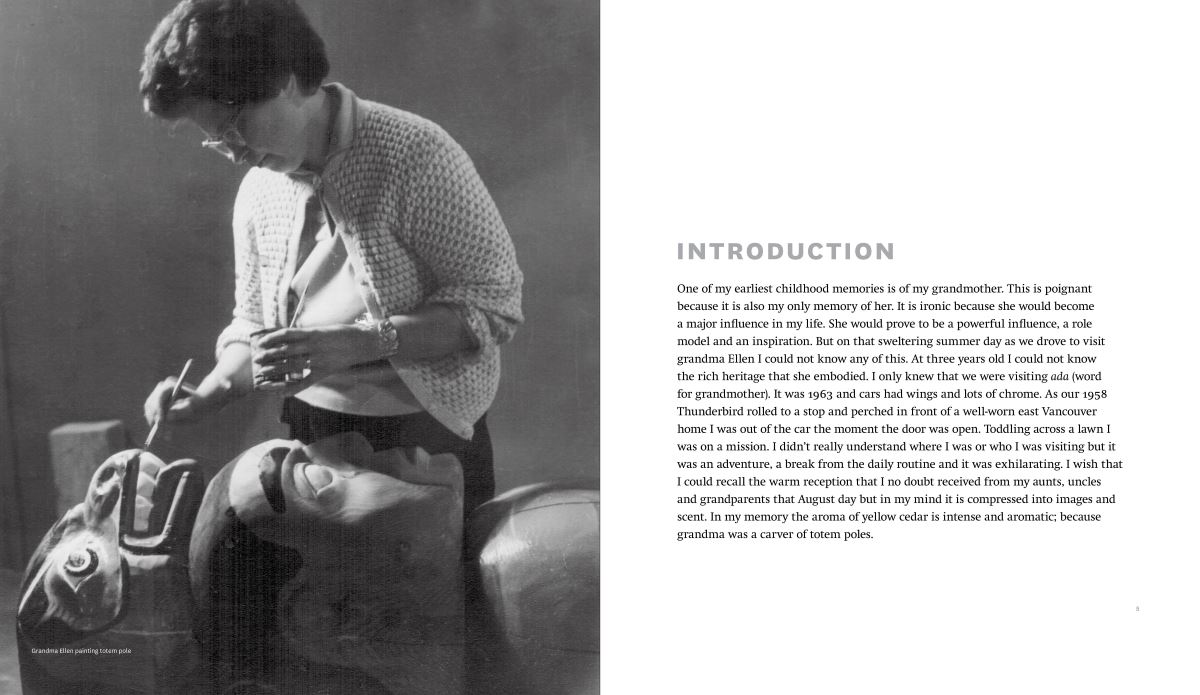

This book tells the story of an Indigenous boy who is separated from his family as an infant, and after a 25 year journey rejoins his family and community, and becomes traditional artist like generations before him. It is a classic tale of the search for family, home and identity. But this story is unique: the boy has the soul of an artist and his creations becomes his family, and he never loses the thread of cultural knowledge and dreams of following in the family footsteps. Over time, through his art he manifests images and carvings that symbolize the family he never knew; allowing him to hang onto a thread of his legacy. Like Odysseus, he finds himself thousands of miles away from his people and can't discern the way home.

One day, in the most unlikely of places, a museum in south Texas, he finds himself staring at a mask of Tsegame that was carved by his grandfather, Charlie James. He immediately recognizes the mask's significance and it speaks to him; not in words but in a spiritual download of cultural knowledge. He realizes that it is time return home and within months he leaves his house and his career, to move to Vancouver; the city of his birth. The ancestors are looking out for him, and just by chance, he moves into a house across the street from where Beau Dick and Wayne Alfred, are carving a totem pole. Within weeks of his return he is apprenticing with two of the most renowned artists of this generation. As time progresses, he becomes a Kwakiutl artist like previous generations of family, and in due course, his children become artists, fulfilling the obligation of passing on the tradition, and the story comes full circle.

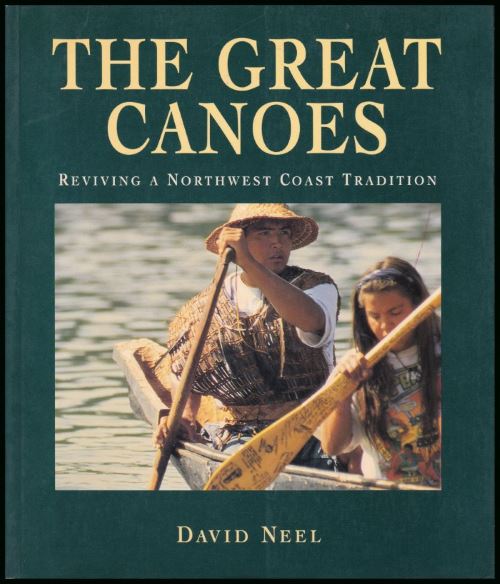

The Great Canoes

Published: 1995

Neel, a member of the Fort Rupert Kwagiutl Nation, is a photographer, writer, and visual artist whose work has been exhibited and collected internationally. He introduces the canoe nations of the Northwest coast among them, the Tlingit, Tsimshian, Haisla, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish; provides a map that shows the extent of their territory; describes the traditional canoes and explains the details of their construction and their significance. Then he takes readers to visit canoe builders who talk about themselves and their work. Full-page color photos complement the text. Annotation copyright Book News, Inc. Portland, Or.

A few extracts from the book:

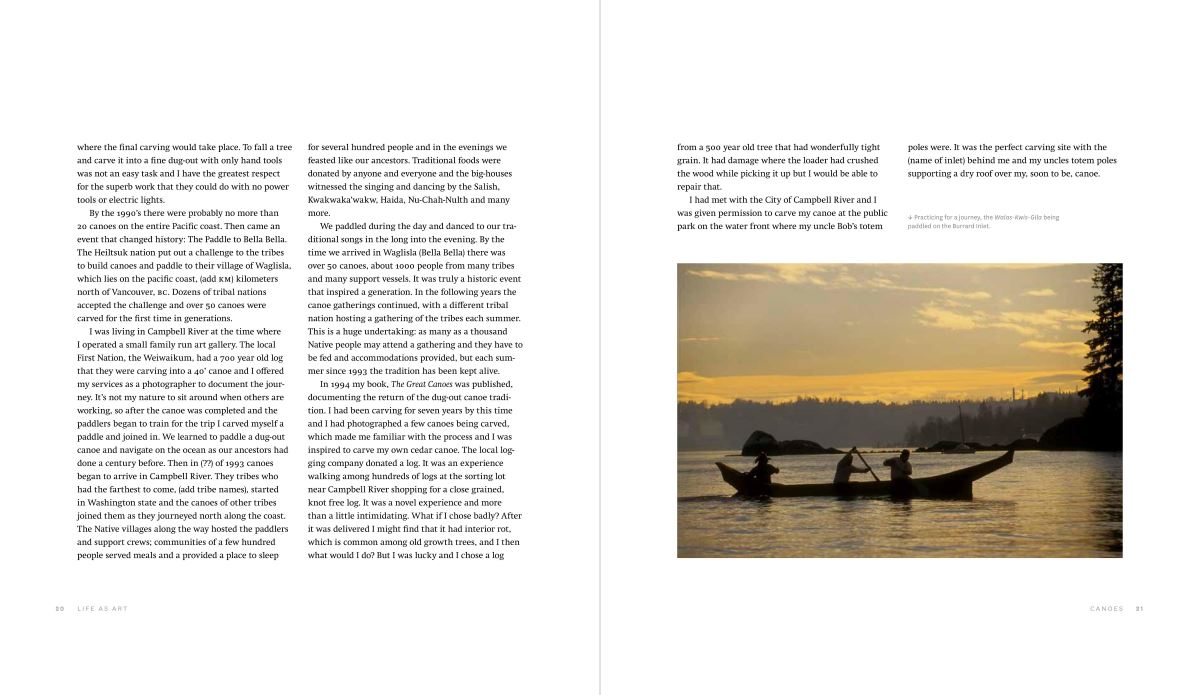

These majestic vessels, crafted from a single log often hundreds of years old, all but disappeared early in this century. It is hard to explain why so little has been written about them, as they are probably the single most important aspect or Northwest Coast culture. To the Kwakwaka'wakw, the Haida, the Coast Salish, the Tsimshian, the Nuu-chah-nulth, the Tlingit and other coastal groups, the canoe was as important as the automobile is now to North America. With one crucial difference: the canoe was a spiritual vessel that was the object of great respect, from its life as a tree in the forest to its falling to earth as a log and finally its landing on the beach as a finished craft. As you read the words that follow, you will understand that respect continues to be a vital aspect of the contemporary canoe experience. The people speaking in these pages are some of those who make up the canoe community that has developed over the last several years. They dream big dreams, setting aside vast periods of time and sacrificing their financial security to live their culture. They have contributed to the return of the great canoe.

The canoe is a metaphor for community, in the canoe, as in any community, everyone must work together. Paddling or "pulling" as a crew over miles of water requires respect for one another and a commitment to working together, as the old people did. All facets of the contemporary canoe experience - planning, building, fund-raising, practicing, travelling - combine to make our communities strong and vital in the old ways. There was a time not long ago when we lived several families to a bighouse and knew our family histories, by memory, for several generations back. We depended on one another for our livelihood. In front of our houses we constructed an awakawis, or meeting place, where we would pass the time, get to know our neighbors, be human together. The contemporary canoe is bringing families, villages and nations together again to work and share. First Nations who have historically been enemies, or have had long-standing issues dividing them, visit one another on our canoe journeys, hosting where once there was animosity. The canoe is helping us to be more human again. We work for something besides income; for a few precious days or weeks we forget about the clock, live by the tides. We stay up late in the villages we visit, singing and dancing, sharing our homes and our cultures. I have never before felt the level of brotherhood and sisterhood that comes out at our canoe gatherings.

I began my canoe for traditional use by my family, and I conceived it as a project I would undertake on my own. I felt that if my ancestor, Charlie James, could carve sixty-foot totem poles with only one good hand, I could manage a twenty-five-foot canoe. In addition, one of my elders advised me that fund-raising and money worries detract from the spiritual aspects of building a canoe. I decided to go ahead, after much soul-searching, because I feel it is important to pursue your dreams. This idealism was to cause me much mental anguish as the time carne to begin carving and the project seemed overwhelming.

The first step was to secure an old-growth Western red cedar. This was done with the generosity of the Ehattesaht First Nation and of MacMillan Bloedel, who donated a log. I journeyed to Elk River, where I had my pick of the logs in the booming ground. The folks there suggested a beautiful thirty-four-foot cedar, which was an appropriate size for my canoe. But I had my eye on an incredible forty-one-foot log that was over six feet in diameter at the butt end and probably twelve hundred years old. It was such a grand old tree: there is truly something magical about a tree that has lived that long on our earth. But as I awaited its delivery to my carving site Campbell River and continued to discuss the project with other carvers, I began to realize that, with the larger log, I would end up with a huge amount of wood to remove. And by cutting away this exterior wood I would be establishing the sides of the canoe deeper in the tree, where there would be branches and knots. So I decided on the smaller tree after all. On a sunny July day it was delivered to my site overlooking Discovery Passage on northern Vancouver Island.

Our Chiefs and Elders

Published: 1992

This magnificent series of images of Native chiefs and elders sharply contrasts with earlier depictions of Natives as 'noble savages' or representatives of a 'vanishing race.' David Neel's photographs of, and conversations with, his own people introduce us to individuals who know who they are and whose comments on the present, coupled with their perspectives from the past, reveal a people with a rich and unique heritage.

Neel has chosen to show many of his subjects in paired images, both in traditional dress, holding the symbols to which they are entitled by hereditary right, as well as in everyday clothing and surroundings. This demonstrates more effectively than any museum display the transforming power of the masks and ceremonial blankets. More important, however, it shows the people as they are - with their lives in two worlds, two cultures - and demonstrates that being Native is not a matter of appearance but rather a way of being.

Many of these individuals were born in bighouses. They reminisce about travelling in log canoes and living off the land. In their conversations with Neel, they talk about their experiences in residential schools, about the potlatch law, and they explain the roles of hereditary chiefs, chief councillors, and elders. But they also have much to say that is relevant to contemporary social, political, and ecological issues.

The commitment and enthusiasm of those who sat for this project are obvious. David Neel's respect for the elders is evident, as is the warmth with which he is regarded by his subjects. And that is what makes this book unique - it is a powerful statement of a surviving race taking its rightful place in contemporary society.

A few extracts from the book:

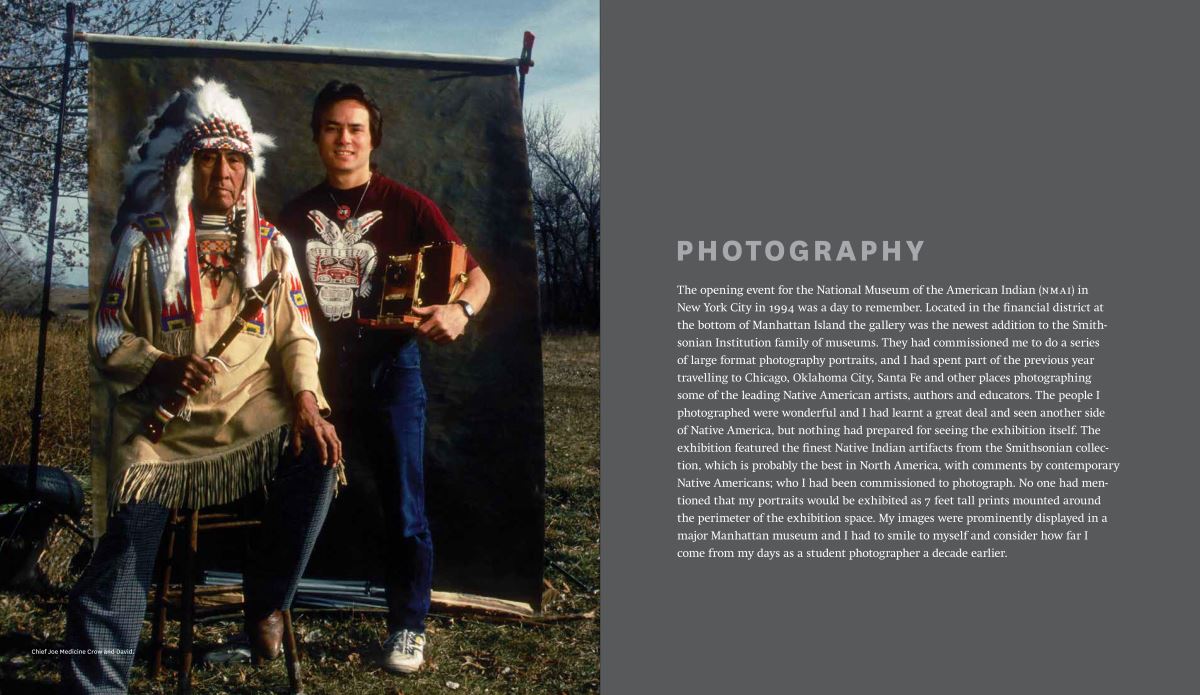

When I set out to photograph the Native leaders of British Columbia, I was not aware of the effect the experience would have on my life Four years and three babies later, a book is born. This body of work is intended to be the antithesis of the 'vanishing race' photographs of Native people this is a statement of the surviving race. It has been my intention to let the people speak for themselves. For this reason the text appears as unedited as possible, as it was told to me between 1988 and 1991. These people serve as the conduits of a knowledge that has come down through time to be handed on into the future. Through their words, it is my hope that you will be able to see beyond the stereotype to the person behind and gain a better understanding of what Aboriginal culture and people are about. History has shown that allowing people to tell their own story is the only way a greater understanding between cultures can occur. The photographs are my interpretation, my vision, of these human beings. I photograph these people as I do all races, striving to go behind the physical appearance to show the humanness of, or common thread between, people.

As I set out to photograph the chiefs and elders, I thought that I would be seeking out the oldest and the wisest. As I met people, it became clear that each had a contribution to make. Like chapters in a book, they come together to tell a story. Research and selection was carried out through word of mouth - what anthropologists used to call 'informants' and 'fieldwork.' By talking to people I would be led from one person to the next. When I planned to visit an area I would talk to one or two acquaintances from that village or tribe and get a name or two. I invariably found my way to someone who became a 'chapter' in this book. I feel that the selection of people included in this collection constitutes a reasonable representation of Northwest Coast elders - at least Insofar as any group of fifty or so people could. In hindsight, it seems as though was being led to the people I needed to meet with. Like the process of photography, this seems extraordinary.

In this book, the chiefs and elders share some of their knowledge about respect. Respect is the foundation for all relationships: between individuals, with future and past generations, with the Earth, with animals, with our Creator (use what name you will), and with ourselves. Respect is both simple and difficult, small and vast. To understand it and apply it to our lives is an ongoing process. This is the most valuable lesson the leaders have for us. It is not a lesson that can be explained with the simple formula, 'Respect is...' For the Kwagiutl, the potlatch is a ceremony which allows us to show our respect in a public setting. We show our respect for the chiefs, the elders, those who have passed, those who have just come, for couples who are joining their fives and families, and so much more. Our potlatch is in a period of rebirth and growth, following the end of restrictions on the potlatch in 1951. The world is growing smaller, and, increasingly, there is the need to respect and understand our neighbors. Our Earth also requires respect. Respect yourself and you will respect others, I am told. The chiefs and elders have shared much with me. In reading their words, and looking at their faces, I hope you will feel they have something to share with you.